Hydroelectric power station Becker Architects

Posted by R U M T O S S E T in Uncategorized on februar 1, 2011

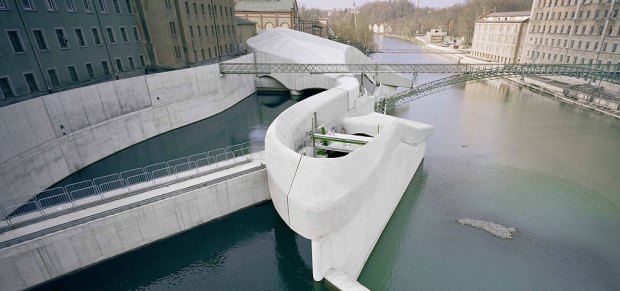

The amorphous form appears both gentle and dynamic, resembling, among other things, a large fish. But it can also be viewed simply as a volume inspired by the motion of waves – as if the structure had taken shape as a flowing, swelling mass and then solidified. The form of this hydroelectric power station traces and dramatizes the channelled dynamism of the water as it flows into the holding basin, down through the turbines, and back into the River Iller. Another obvious association is with eroded stone; in the surrounding Allgäu region, not far from the Alps, such isolated rock formations are a common sight.

This distinctive outer form owes its existence to the planning authorities. Originally, a specialist engineering firm had completed plans for a high-efficiency hydroelectric facility on the left bank of the river in Kempten to replace an old power station from the 1950s. Only after this had already been drawn up did the authorities decide that the new power plant should fit into the natural setting of the River Iller as well as harmonizing with the adjacent ensemble of listed 19th-century buildings comprising a spinning and a weaving mill.

The design by Becker Architects neither tries to render the power station invisible, nor to overstate its technical power. As an autonomous piece of contemporary architecture, it allows the old industrial buildings and the river landscape to retain their identity, but without denying its own. It accentuates the dividing line between water and building, using an architectural idiom of metaphors associated with the river landscape. Appearing to be made out of soft, malleable material, it establishes a semantic link between the use of renewable hydroelectric energy and the gentle method of harnessing that energy. Other ecologically significant aspects were also prioritized, such as the inclusion of a fish ladder and measures to minimize noise.

The flowing exterior consists of a three-dimensionally curved reinforced concrete shell. Resting on slide bearings, and with a gap between it and the power station structure, the shell is capable of compensating differences in longitudinal deformation with respect to the substructure. Rough boards were used for the interior formwork, while the exterior was spray-coated, giving the surface an almost velvety character well suited to its shape, avoiding harsh light effects. This in turn assures a smooth transition from the shell to the pale, fair-faced concrete walls enclosing the power station in the water. To minimize disruption of the homogeneous outward appearance, necessary openings were kept as small as possible. A lightweight concrete section, removable by mobile crane if drifting debris accumulates, also fits into the overall form. This immaculate impression will not last long, however, as the structure will soon age, changing its appearance.

What will remain is the dynamic gesture with which the shell connects the two ends of the power station, diving under the lattice arch of an existing steel cable bridge, thus allowing the original ensemble of five different bridging structures to be preserved. The interior is also an impressive sight, although different in character. While the outside plays with biomorphic associations, the interior reflects the technical quality of the turbines, which are also visible. This is certainly due more to pragmatic than to aesthetic considerations, as the inside of the power plant is far less of a public place, although guided tours are offered – an opportunity taken up by many in the months after the project was completed. Nonetheless, the interior, too, evokes fittingly water-related images, as the lateral ribs reinforcing the construction recall the frames of a ship’s hull. The tension-filled volume of the exterior is seen in reverse, with a varied sequence of cramped and open, high and low spaces, and there are also views of the water. Thanks to a new foot- and cycle-path along the river, the power station, which will supply 3000 households, can be viewed at any time – a sight well worth seeing, including at night, when it is dramatically lit.

Takayuki Hori: Oritsunagumono

Posted by R U M T O S S E T in KUNST, museum on februar 1, 2011

Behold the work of Japanese student Takayuki Hori which won first place in the 2010Mitsubishi Chemical Junior Designer Competition. The collection, entitled Oritsunagumono (things folded and connected) involves the skeletons of eight endangered species which are delicately printed on translucent paper and then folded in an origami fashion to represent the animals. A poignant and grim reminder of life’s fragility. What a brilliant project.

Puckelball Pitch, Malmø

Posted by R U M T O S S E T in URBAN LIVING on januar 31, 2011

Is Dr. Seuss still alive, hiding out in Sweden, working as an urban planner? Not quite. The puckelball pitch made of artificial turf is a design concept by artist Johan Strom, who created this field in Malmö, Sweden as a metaphor for life:

“Many live under the belief that life is a fair playing field, that both pitch halves are just as big and the goal always has at least one cross. But ultimately the ball never bounces exactly where you want it to and the pitch is both bumpy and uneven.”

The rolling landscape of the field is meant to inspire imaginative play and to encourage fair competition between skilled and unskilled players, young and old, boys and girls. It was nominated in the Making Space 2010 competition that gives prizes to the best architectural and designed spaces for children.

Every city in the world should be lucky enough to have a field like this !